Support helped women and children integrate into the wider community

The Methodist Woman’s Missionary Society (WMS) was an organization that did mission work both in Canada and abroad. A large part of the mission work centered on schools and hospitals. In Canada, the WMS appointed missionaries (“WMS workers”) to support immigrants, Indigenous communities and people living in poverty.

In Vancouver, a significant part of their work focused on supporting women and children recently arrived from Japan and China, helping them adapt to their new home. According to a 1935 interview with Etta DeWolfe (WMS worker appointed to the Vancouver Japanese Mission), the WMS felt that Japanese children needed to be taught English and Christian tradition and culture, so that they could enjoy Canadian life and become an integral part of it.[15]

In November 1909, the WMS purchased a house at 652 Keefer Street. This was the “missionary residence” where WMS workers involved in the Methodist “oriental work” lived. The missionary residence hosted social gatherings for women in the Japanese and Chinese communities.[16]

In 1912, Nobu Kusama—later Nobu Shimotakahara—came to the mission to assist Miss Preston. In the church’s increasing role as an agent of assimilation, the missionary residence came to be seen as a model for the community:

“We rejoice to know that in the community we have come to stand for high ideals and an uplift towards the good. It is said that the Buddhist women in their monthly meetings aim to have helpful talks, because they wish their women to improve as much as do the women who attend the Christian women’s meetings.”[17]

As the work grew in scope, the WMS appointed Etta DeWolfe to work with them. Miss DeWolfe specialized in kindergarten education, working with both the Powell Street Church and the nascent Fairview mission, beginning in 1917. Her work expanded to include other Japanese communities in the Lower Mainland. She dedicated herself to this work until retirement in 1938.

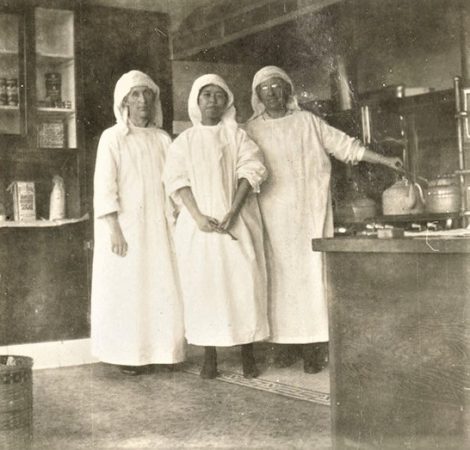

During the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic – when Japanese Canadians were unable to receive treatment due to hospitals favouring Caucasian patients – WMS volunteers stepped up in the face of this serious health threat to the community. WMS workers helped set up a temporary hospital (at Strathcona School) for the Japanese Canadian community and took responsibility for the nursing staff and the kitchen.

Women’s ministry and services to children in the Japanese community continued to grow. The WMS organized Saturday school, CGIT, Mission Band and Explorers. They sponsored conferences for women. Mothers’ groups emerged. As one publication observes, “Their contribution to children’s education led parents to the church indirectly.”[18]

In 1922, Florence Bird joined the women and began work at the Fairview mission base at Yukon Street and West 4th Avenue.

In 1925, the Vancouver School Board announced that it would segregate Japanese children from public classrooms. The board’s reasoning was that there was a lack of fluency in English among Japanese Canadian children in the schools. United and Anglican churches responded by committing to teach children for two full years before entering public school.

During the Second World War, the WMS was keenly aware of the grave injustices being inflicted on Japanese Canadians who were sent to internment camps. WMS workers went with community members to internment camps to set up and teach kindergarten, and lead groups for mothers, children and youth. Their efforts were aimed at providing the community with some of the supports they had benefited from on the coast.